SOUTH BRUCE – Members of an elite group of field workers from the Toronto Zoo are monitoring bat activity in South Bruce to assess their population, health and breeding status.

The Native Bat Conservation Program, part of the Toronto Zoo, receives sponsorship and support from the Nuclear Waste Management Organization (NWMO). Both organizations are working in partnership to further their knowledge and the conservation of bats in Ontario.

“Conserving our bats means first finding out their current population levels and requirements, so we can ensure that appropriate habitat is available and help people avoid harmful activities,” the zoo’s website said. “The Native Bat Conservation Program at the Toronto Zoo is working with a number of projects and partners to contribute to our understanding of Ontario’s bats.”

Toby Thorne, coordinator of the bat program, welcomed Midwestern Newspapers on their latest field trip to South Bruce on July 19 for an exclusive look at what they do.

After a short hike into a known location of bats near the Teeswater River, the group began their evening by setting up several Triple High Net Pole Systems.

Bridget Sparrow-Scinocca, a member of the field team, erects a mist net to safely capture bats on July 19 in South Bruce. (Cory Bilyea Photo)

The portable system consists of poles and an associated hoist system capable of creating a huge mist net 24 feet (7.3 metres) tall. In order to remove a bat or bird from any net, a pulley system quickly and carefully collapses the net stack until the animal can be reached. The nets can be set up, raised, lowered, and packed up by a single person. Each tier of every net can be individually adjusted and tensioned in seconds for any bag-overlap desired and to prevent sag.

The team explained this process as a safe way to capture bats that will not hurt them or damage any of their delicate wing structures.

The team was excited to have caught three bats on this particular field trip, expressing their delight at what they called a very successful evening. But, unfortunately, they sometimes don’t catch any.

The three bats that they were able to study were all little brown myotis bats, a species currently classified as a “species at risk.”

According to Ontario’s website, white-nose syndrome (WNS) has been the major cause of documented mortality in little brown myotis since the disease arrived in North America in 2006.

“Population size and trends for this species across its global range are not known but were assumed to be abundant and stable before the arrival of WNS. Therefore, any declines that have occurred can only be inferred from pre- and post-WNS monitoring of known hibernacula,” states the website.

“Even then, a lack of baseline population information precludes an evaluation of what proportion of the population is represented by such inferred declines, since not all hibernacula are known, let alone receive regular monitoring attention. Moreover, most underground hibernacula, mainly caves and mines in North America, have never been surveyed for bats.”

WNS is caused by a fungus believed to have been mistakenly brought to North America from Europe. This fungus grows in cold, humid environments, such as cafes and mines where little brown myotis bats are known to hibernate.

“The syndrome affects bats by disrupting their hibernation cycle so that they use up body fat supplies before the spring when they can once again find food sources,” states the Ontario.ca website.

“It is also thought that the fungus affects the wing membrane, which helps maintain water balance in bats. Because of this, thirst may wake bats up from hibernation, which may be why those infected with the white-nose syndrome can be seen flying outside caves and mines during the winter.

It’s believed that bats are more than 75 per cent of Ontario’s hibernation sites are at high risk of disappearing due to WNS.

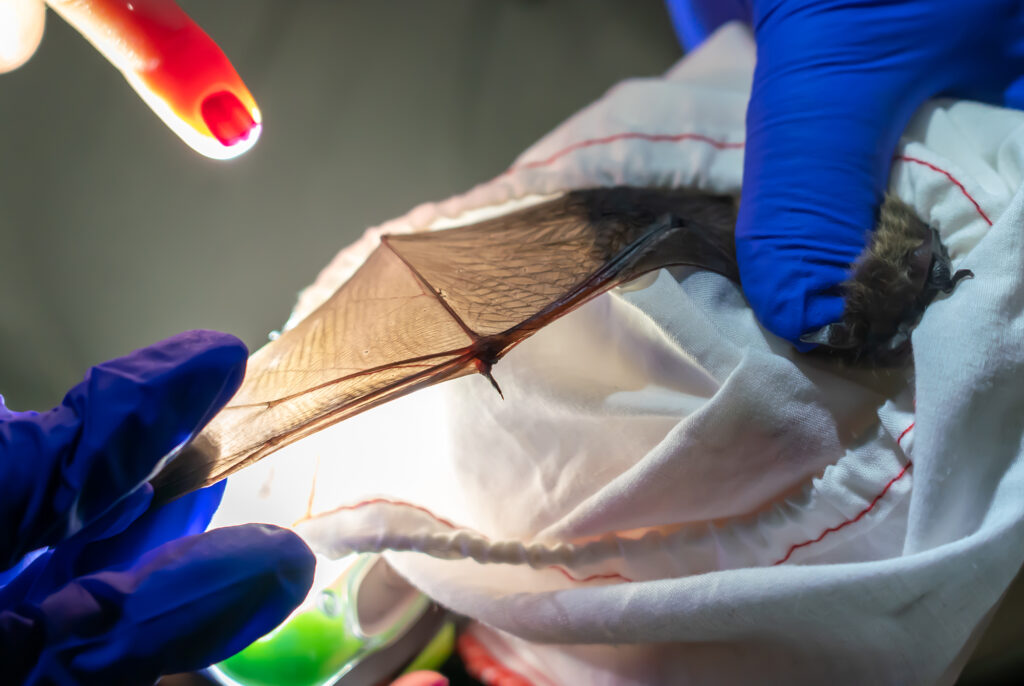

A female little brown myotis bat has her wingspan measured and checked by members of a field team from the Toronto Zoo on July 19. (Cory Bilyea Photo)

The team from the Toronto Zoo gently checked the tiny mammals for weight and wingspan.

Since all three of the temporarily caught bats were female, they checked their nipples for signs of lactation and the possibility of recent birth, which is a positive sign that the species is still fighting back against extinction.

The team chose the largest of the three captures to attach a transmitter to, a process that included trimming the hair off of her back, gluing a radio transmitter to her, and putting the trimmed hair back over the top of the small white bulb with an antenna attached to it.

Thorne said that the transmitters usually fall off in a few hours, so time is critical when they are attached to document where the bat travels in the area.

Thorne updated Midwestern Newspapers in an email in the days following the July 19 outing, saying, “we did have a successful time following the tagged bat, and are pleased with the results.”

All of the bats were treated humanely and released within half an hour of capture, unharmed.

Bat conservation specialist Toby Thorne trims the hair off the back of a little brown myotis bat to attach a radio transmitter during a Toronto Zoo field study in South Bruce on July 19. (Cory Bilyea Photo)